"TALES OF CHRISTMAS PAST"

"THE 17TH CENTURY"

Christmases of 'Yore',

(What's gone long before)

When Christmas bells rang

Or...when no songs they sang;

When there was reverent chanting

Or rejoicing and dancing.

What did they eat?

Was it sour or sweet...

...Surrounding that 'Night'

so 'Sublime'?

This was once

End of the Harvest,

Toasting the best, most and broadest.

Feasting and Merriment

The very heart of its sentiment!

In that dark of the year,

Reigned yet Mirth, Joy and Cheer,

With dancing and singing,

(Plus fat turkeys)*, all bringing

An Embrace ...

to this 'Night' so 'Divine'.

"THE BRITISH CHRISTMAS, 1600 - 1700"

The Tudors of the 1500s had held Christmas quite seriously,

their rich and festive customs continuing into the Stuart reign of the early 1600s.

Christmas encompassed 12 days of lavish and expansive celebrations -

generally centering around "the feast", with all manner of food and beverage.

Roasted boar’s head was a favorite, along with peacock, swan, larks, partridges,

quails, roast beef and prawn pasties. It is said that Henry VIII found "turkeys"* –

and soon they too were the center of feasts.

Tables were also topped with a multitude of fruits, sticky sweets and cakes,

including 'mince pie' (a mixture of meat or fowl, fruit and spices baked in pastry case) -

and 'plum porridge' (beef broth with prunes, raisins, and currants) for the poor.

"Still Life with a Turkey Pie", Pieter Claesz, 1627

A Few Early 17th Century "CHRISTMAS CUSTOMS" :

There were plays (known as 'masques').

There were games and much gambling.

Although monastic chanting remained,

the revelers wassailed through the streets and villages.

And they sang early Christmas carols.

These might include :

"While shepherds watched their flocks"

"I saw three ships come sailing in"

"The First Noël"

"In dulci jubilo" (“Good Christian Men, Rejoice”)

It is recorded that by 1605, Christmas trees were 'the thing', especially on the Continent.

Historical records suggest that in Strasburg, fir trees were set up in the parlors and

draped with roses cut out of colored paper, apples, wafers, gold-foil, and sweets.

However, the Christmas tree did not reach its full British prominence in the 19th century.

Evergreen boughs, however, were brought in the night before Christmas.

Then there was the bizarre custom of appointing a "Lord of Misrule",**

"crowned" by receiving a bean baked inside a cake.

The "King", and often his "Queen" (she just got a pea), would oversee

the "Feast of Fools", a holiday that reversed the order of social hierarchy.

This Lord and his court of merrymakers paraded down streets, wearing masks and

playing instruments, then brought their song and dance inside, where

the Lord of Misrule would command (and must be obeyed) that all have more drink, food and fun.

This is depicted above in c1640 painting "King of the Bean" by Jacob Jordaens.

The "giving of gifts" between the nobles and monarchs was already a formal court ceremony -

the day of giving being New Year’s Day - whilst a large Yule log burned in the fireplace.

James I, son of Mary Queen of Scots, added to these Christmas festivals

an edict that "nobles also give gifts to the poor".

IN SHORT, THESE 12 DAYS WERE MEANT TO BE ONE of

"JOYOUS INDULGENCE and GENEROSITY!"

But before one could partake of such merriment...

- be they noble or peasant -

current fashion dictated that both he and she be literally "laced" into tight clothing.

For women a bodice or 'stomacher' was the fashion, for gentleman, the weskit.

For this purpose was the bodkin – the lady to the right shown threading her bodice!

Two Fine & Rare Early 17th Century Silver "Marked" Bodkins :

The top, James I / Charles I, with Maker’s Mark G, also with Ear-Spoon

The bottom, James I, c1610-20, with Ear-Spoon, Maker’s Mark Partially Cast (S?)

The 'ear-spoon' could collect ear wax to strengthen the ribbons for threading.

Above left, a lady is shown lacing herself into her corset with a bodkin and ribbon.

And, as the Scriptures say, in the "Beginning", there had to be

"LIGHT" :

For several hundred years, Europe had beenoverwhelmed by the plague.

In 1593, William Shakespeare moved to London. In that same year,

London lost 10,000 people to the plague, and closed all theaters and public markets.

(The times were in many ways not unlike our own in 2020-21).

In desperate attempts to uphold 'righteousness', the British clergy ordered

destroyed all the church 'pricketsticks' of the Middle Ages, considering them

"monuments of superstition".

In their place came the 'socket-form' candlesticks we still use today.

Most early 17th century copper alloy candlesticks used in England

were of Continental origin.

The earliest remaining British candlesticks generally date from c1650.

All continued to be small - mostly 5 to 8 inches - throughout the 17th century.

Three 17th Century Copper Alloy Candlesticks :

Left : 'Capstan' Candlestick, Spain or Portugal, 17th Century 5” High, 13.1 oz.;

Middle : A Very Good Quality 'Heemskerk' Candlestick, Dutch, c1650, 8-5/8” High, 42.1 oz.

Ref : ‘Domestic Metalwork. 1640-1820’, Gentle & Feild, p. 123, Pl. 12, for an almost identical example;

Right : Rare Spiral Twist Stem Candlestick, Spanish, c1680, 6” High, 14.1 oz; spiral twist with hexagonal base.

All spiral twists are rare and desirable. Ref : ‘The Brass Book’, Schiffer, p. 189, Pl. A, for a similar example

Now, A Bit About The All Important

"FEAST" :

You already have some idea of that the table would be like.

However, also banned by British clergy was the use of ';table forks'

for eating all this sumptuous food.

Forks had existed since Roman times (usually two tines), and were in use in France by the 1500s.

At that time, British clergy deemed it

"an insult not to touch God’s meat with one’s fingers".

The word fork also sprang from the Latin word "furca", meaning "pitchfork".

But the survivor was the "sucket fork",

just for the eating of "sweetmeats", or "succade" - sugared sticky fruits in syrup

William and Mary Silver Sucket Fork Adam King, London, 1691

Lit. : Illustrated The Collector's Dictionary of the Silver and Gold of Great Britain and North America,

Michael Clayton, 1971 Pl. 60, p. 36.

Forks as we know them today, but with three tines, did not appear until 1667 (small), and as dinner about 1690.

These"sweetmeats", as mentioned above, were served at a final course of desserts called "banquets".

Banquet tables, usually in a space separate from the dining, were covered with

fruit, cakes, biscuits and sticky preserves, all of which featured very expensive imported sugar.

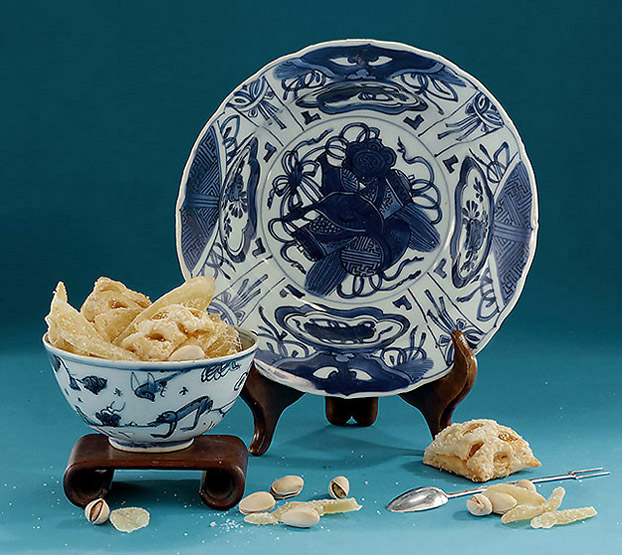

These sticky sweets were often served in imported Asian porcelain of the period :

Wanli, Transitional, early Japanese, and from about 1670, Kangxi.

(The long white gnarly pieces above are candied citrus rinds).

Ming Dynasty Kraak Porcelain Large Klapmuts Bowl,

Rinaldi, Group V / Wanli, China, c1600-20, 8.5" Wide

Ming Dynasty Ko-Sometsuke Deer & Monkey Bowl, Jiajing, c1522–1566,

with Sweetmeats (Candied Fruits), Nuts, Pastries, and a

1691 Silver Sucket Fork, Adam King, London

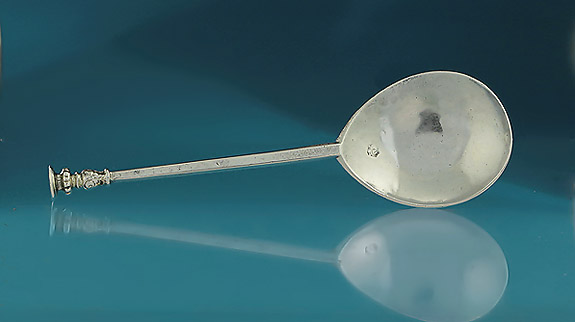

Besides the sucket fork, the only other eating utensils provided for the feast were simply

a sharp knife, and

a spoon with fig-shaped bowl,

made from latten, pewter, wood - or for the wealthy, silver

James I Silver Seal Top Spoon, William Limpanny, London, 1613

Mark WL conjoined in a shaped punch / 1.75" Long / 1.6 oz.

Provenance : Descendant of William Beckford & The Dukes of Hamilton

And The Accompanying

"IMBIBING" !

In the c1640 painting, "The Bean King" (shown at the beginning),

five guests are drinking glasses called "roemers", and two from stemware.

These glasses are also shown immediately above, in the 1607 painting by Clara Peeters,

also depicting "sweetmeats" and a small socket-form candle.

Very few early 17th century drinking glasses have survived.

However, you will also note (in "The Bean King") several ewers of pewter and stoneware.

Fortunately, many of the stoneware still exist, as well as a few leather and wooden tankards.

A 17th Century Continental Westerwald Jug, c1650-1690

heightened in blue and manganese, and

A Silver-Mounted Black-jack Tankard, Impressed Date 1605

with initials B I and E B, and below I W

THEN CAME AN ABRUPT END TO ALL "MERRIMENT".

From 1647 until 1660, Christmas and all its customs – and gaiety and feasting –

were outlawed – made illegal – completely banned.

Even music. Christmas greens and the Yule log were forbidden.

This was courtesy of OLIVER CROMWELL, Britain's Commonwealth ruler, (below left),

who deemed all celebration pagan, and demanded the return to only quiet and piety at Christmastime.

The bells no longer rang

And songs – they no longer sang

However in 1660, joyous "indulgence" reappeared

with the return of CHARLES II to the throne (above right).

Back was the feasting, the dance, wassailing, the Yule log, bells ... and overseeing it all was

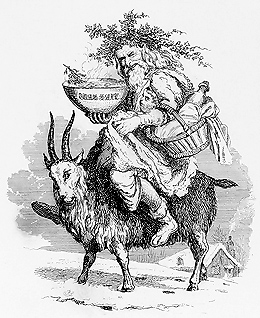

"FATHER CHRISTMAS"

"Father Christmas", the ancient English folklore "personification" of Christmas,

with gaiety, great feasting and good cheer,

emerged in the mid-17th century as a "human figure" rather than a theme.

He had, at this time, no relationship with gifts, or children – but more feasting and merry-making,

Eventually, in the 19th century, this new “figure” of "Father Christmas"

took on the role of the "gift-giver" - and "Santa Claus".

The "SPICES" :

In the 17th century, spices were a sought after luxury -

primarily as food stored in spring houses often got a bit ripe after a few days.

Among the most important of the spices was nutmeg.

In fact, in 1674, Holland traded the entire island of Manhattan for two small islands in the East Indies

that had a very small British nutmeg trade.

Well, Manhattan...plus a little sugar.

Also about that time, a small silver box carrying nutmeg became an essential

part of the British gentleman's dress to flavor ales, wines -

and the new very festive FAVORITE from India, "PUNCH"!

William & Mary / William III Silver 'Teardrop' Nutmeg Grater, c1690-1700,

the cover with scratched owner’s initials 'L*H' (Left)

William & Mary Silver Tubular Nutmeg Grater, Thomas Kedder, London c1690,

the cover with a Tulip (Right)

William & Mary Silver 'Teardrop' Nutmeg Grater, Thomas Kedder, London c1690,

engraved with Tulip & Tudor Rose (Below)

The word "PUNCH" is said to have derived from the Hindu word "PANCH", for five,

consisting of five ingredients - basically "sweet, sour, bitter, weak, and alcoholic".

There were several recipes - some involving tea or milk. The most usual

combination included water, sugar, limes, lemons or oranges, spices and spirits.

It could be served warmed or chilled.

"NUTMEG" would have been added from early silver boxes, as those above.

The "SPOONS", from c1667-1700 :

In the early 17th century, spoons with fig-shaped bowls, seal tops, slip tops, or rarely apostle tops

had been the fashion. Your single spoon would have traveled about with you - silver if wealthy.

In its absence, a house spoon of wood, pewter, or latten would be provided.

With the return of Charles II to the throne also came many French customs.

Among those was the "trefid" spoon, sometimes called the "French forked" spoon.

The earliest English trefid spoon recorded is 1662 -

followed in the 1670s by the wonderful "lace-back" spoons.

And this is just in time!

as the first recorded serving of ICE CREAM,

was at the 1671 banquet table of Charles II for the Feast of St. George.

"The King was served one plate of white strawberries and one plate of ice cream.

So rare was this treat, it was only served to the top table.

Everyone else had to just watch and wonder."

Pair Charles II Silver Lace Back & Front Spoons, Robert King, London, 1678

Existing pairs of lace-back trefid spoons are exceptionally rare,

especially those that retain good detail to the decoration.

One has to "wonder" if these might have had the privilege of tasting early "ice cream".

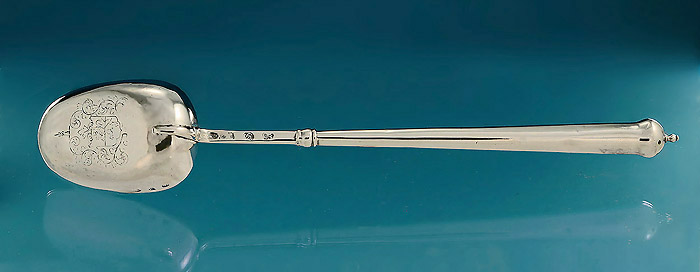

The "GRAND FINALE of SPOONS", c1667-1700 :

Canon-Handled "Basting" or "Serving" Spoons, with hollow tubular stems and oblong bowls,

were introduced in the late Charles II period, made until c1725,

after which time they became larger versions of the current tablespoons (dog-nosed, Hanoverian).

Small blow holes at the stem terminals have been reported to allow heat to escape both

when assembling, and when serving with hot foods.

Although known as "basting spoons", they were also used as "serving spoons".

A pair in the Royal Collections is listed as "for Plum Broth".

William & Mary Silver Canon-Handled Basting Spoon, Lawrence Jones, London, 1697,

the bowl with original coat of arms, 15" Long / 5.5oz.

A Jones canon-handled spoon with different arms is illustrated, London Silver Spoonmakers, 1500-1697,

Timothy Kent, p.53, fig.74

17th century England had returned to the joyous Christmas celebrations of the past.

However, earlier lavish and unbridled revelries never again reached their previous zenith.

As has been intimated :

Maybe "The Grump Himself" stole it?!

But then, they did get "PUNCH!"

To be continued.......

Meanwhile, please have a seat on our favorite Charles II Walnut Stool, c1670 :

Additional Notes on the Early 17th Century Christmas :

* Turkeys, native to the Americas and domesticated by the Aztecs, had come to Europe via Spain.

Henry VIII is supposed to have been the first to sit down on Christmas Day and as early as 1573.

And in 1573, Thomas Tusser noted that turkeys had become common at Christmas.

Turkey was included in Gervase Markham’s 1615 housekeeping guide "The English Housewife",

while "The London Poulters’ Guild" records show company clerks were given them as Christmas presents.

By the 1640s, turkeys still were the equivalent of three days’ wages for a craftsman.

** "The Lord of Misrule" or "Bean King" was based on an ancient Roman agricultural festival custom

This mid-December festival was called Saturnalia, honoring the agricultural god Saturn,

(pictured below with his scythe in a 2nd century AD bas relief), and

and is the source

of many of the traditions we now associate with Christmas, including the "Lord of Misrule".

Saturnalia began as a single day, and by the late Republic (133-31 B.C.) had expanded to a weeklong

festival beginning December 17. (On the Julian calendar, which the Romans used at the time, the winter

solstice fell on December 25.) During Saturnalia, Romans, including their slaves, did not work.

Instead, they decorated their homes with wreaths and greenery, spent the days gambling, singing, playing music,

feasting, socializing and giving each other gifts. The celebrations were often riotous.

In some households, a mock king was chosen: the Saturnalicius princeps, or "Leader of Saturnalia",

sometimes also called the "Lord of Misrule". This leader was usually a lowlier member of the

household, and would be responsible for making mischief during the celebrations.

The idea was that he ruled over chaos, rather than the normal Roman order.

Among his antics were insulting guests, wearing crazy clothing, chasing women and girls, etc.

The method of choosing the mock king was through hiding coins or other small objects in cakes.

Paintings, in the order of appearance :

King of the Bean, Jacob Jordaen, c1640, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

Still Life with a Turkey Pie, Pieter Claesz, 1627, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

The Artist and His First Wife, Isabella Brant, in the Honeysuckle Bower, Peter Paul Rubens, 1609-10

Mother Lacing Her Bodice Beside a Cradle, Pieter de Hooch, c1660, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

A Girl with a Candle Drawing Aside a Curtain, Godfried Schalcken, 1670, Private Collection

Still Life with Porcelain, Sweets and Nuts, Osias Beert, Private Collection

Stilleben mit Façon-de-Venise-Glas, Römer und einer Kerze (Still life with dainties, rosemary,

wine, jewels and a burning candle) Clara Peeters, 1697, Private Collection

Oliver Cromwell, 1599-1658, Robert Walker of Cromwell, Cromwell Museum, Huntingdon, UK

Charles II of England, Simon Pietersz Verelst, 1670 and 1675, Royal Collection, Public Domain

A Merry England Vision of Old Christmas, 1836, Robert Seymour (1798 – 1836)

Bas Relief of Saturn with Scythe, 2nd Century AD, Capitoline Museums, Rome; Photo, Jean-Pol Grandmont

(All Paintings & Engravings Courtesy of Creative Commons)

Inventory Photography : Millicent F. Creech

For "Tales of The 18th Century British Christmas", Please Click Here :

And the "19th Century", Click Here :

|